EDUCATION & GENDER EQUALITY INSIGHT

The urgency of educating women and girls has been vocalized by scholars, organizations and agencies that concentrate on social development.

The United Nation in particular has identified such urgency through its UN Sustainable Development Goals that

stress the importance of addressing the gender gap in education, as seen in SDG (4) Quality Education

and SDG (5) Gender Equality.

Over the past decade, Indonesia has made great progress in achieving gender equality in the education sector. Growth in Indonesia’s education sector has proliferated and access to education has skyrocketed, boasting higher participation across demographics.

In particular, female participation in education has improved dramatically, with gender parity index (GPI) showing significant improvement from 1970s until 2019.

However, despite increased access, the quality of education remains stagnant.

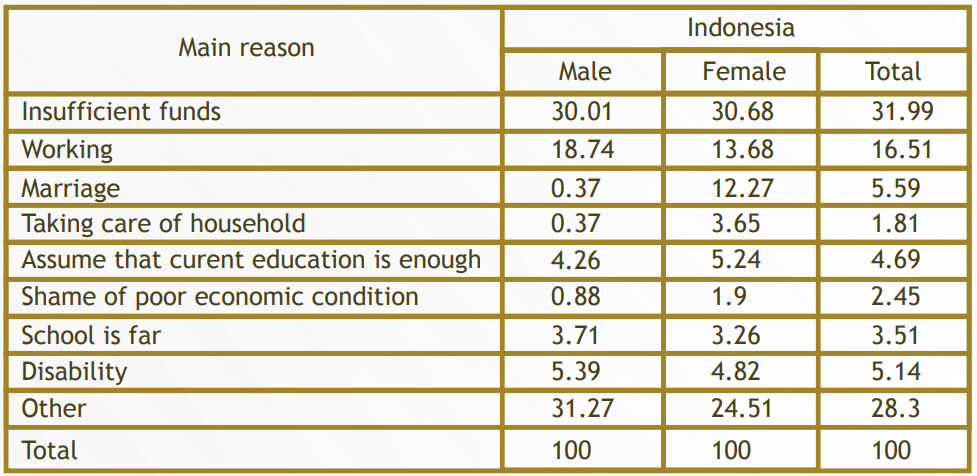

According to a study by the World Bank on gender in education, disparities in financial socioeconomic status and geographic factors appear to be crucial determinants to school completion by students. The main reason for dropping out by gender are as follows:

Source: SUSENAS, 2017 (Adapted from World Bank)

Indeed, the structural nature of the above-mentioned barriers make gender inequality in education difficult to overcome. However, assuming a multi-level and multi-dimensional critical analysis of power allows for possibilities and conditions for transformative action to occur, thereby underpinning the process of empowerment.

Power, in essence, emanates from multiple focal areas of varying natures, and not wielded by individuals or groups through sovereign acts of domination.

There are different forms of power: power within, power to, power with, and power over.

‘Power over’ is a form of power that relies on coercion and dominance, and is disempowering for its target. On the other hand, ‘power within’, ‘power to’ and ‘power with’, can be seen as an exercise of a more empowering process, with the latter two as respectively embedded in individual and collective action.

Moreover, the dimensions of power can be demonstrated as overlapping in: (a) personal sphere: empowerment occurs by virtue of overcoming the consequences of internalized oppression and cultivating a sense of self; (b)

relational sphere: empowerment occurs by virtue of fostering the capacity to negotiate and have an impact on the dynamics of the relationship and the decisions made within; (c) collective sphere: empowerment occurs when individuals work together to produce a larger influence than they might have done separately.

In areas where ‘power over’ is exercised, there is resistance, and when power is resisted, the process of empowerment becomes clear.

The imposition of a social order called the patriarchy is a gendered form of power that has dominated all aspects of life.

This process is governed by social norms derived from the duality of masculinity and femininity.

Women are associated with femininity, in that they REFERENCES are communal, warm and subservient, whereas men are associated with masculinity, in that they are agentic, instrumental, and competent.

Such categorization tempts faulty assessments of people, forming a social “blueprint” in which men and

women are expected to act within the constraints of their assigned attributes, thereby creating gendered stereotypes that affect the roles they occupy in the society.

What is more, stereotypes and power are mutually reinforcing. A 2020 survey with 2000 respondents regarding gender roles and expectations in an Indonesian household finds that a majority of respondents’ expect the wife to take the duties of performing household and care work, whereas the husband is to take the role of breadwinner and earn money for family needs.

The manifestations of such categorization can be seen in the high numbers of girls dropping out of school due to marriage, domestic work, and the assumption that girls do not need to complete their education as their expected roles do not extend to public and professional life.

Without education, women and girls are limited in their abilities to contribute economically and politically, strengthening structural barriers, as they are forced to rely on their male counterparts for livelihood, furthering the gendered division of labor, and their marginalization in the society, while simultaneously promoting the idea that women are incapable of participating in public and professional life.

Accordingly, gender equality “entails reflecting critically on the causes and consequences of these gendered forms of power … and transforming those [causes and consequences] that do not provide women and men with lives they have reason to value.”

Such transformation relies on the ability of marginalized peoples, particularly women and girls, to make choices and exercise their agency, and the structural settings and conditions that afford women and girls the opportunity to partake in their own empowerment within the different spheres of their lives.

It becomes the duty of those with access to resources to redistribute their power to not only provide women and girls with a safe space to explore and create ideas, but also a space to build life-long competencies.

As they procure vital knowledge, skills, and abilities to work independently and identify their own concerns, they become more confident in engaging in public and professional life, asserting their own agendas, and consequently contributing to the well-being of society.

Thus, youth and community work that focuses on transformative education and building the capacities of girls to face barriers, alongside structural changes, become crucial in achieving SDG (4) Gender Equality and SDG (5) Quality Education.

REFERENCE

Coburn, A., & Gormally, S. (2017). Understanding Power and Empowerment. Counterpoints, 483, 93-109. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/45177773.

Fiske, S. (1993). Controlling other people: The impact of power on stereotyping. American Psychologist, 48(6), 621-628. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.48.6.621

Hentschel, T., Heilman, M., & Peus, C. (2019). The Multiple Dimensions of Gender Stereotypes: A Current Look at Men’s and Women’s Characterizations of Others and Themselves. Frontiers In Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00011

Monkman, K. (2011). Framing Gender, Education and Empowerment. Research In Comparative And International Education, 6(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.2304/rcie.2011.6.1.1

Rowlands, J. (1995). Empowerment examined. Development In Practice, 5(2), 101-107. https://doi.org/10.1080/0961452951000157074

Unterhalter, E. (2022). Fragmented frameworks? Researching women, gender, education and

development. In E. Unterhalter & S. Aikman (Eds.), Beyond Access: Transforming policy and practice for gender equality in education (pp. 15-35). Oxfam.

VeneKlasen, L., & Miller, V. (2002). Power and empowerment. In A New Weave of Power, People & Politics. Practical Action Publishing.

Yarrow, N., & Afkar, R. (2020). Gender and education in Indonesia: Progress with more work to be done. World Bank Blogs. Retrieved from https://blogs.worldbank.org/eastasiapacific/gen der-and-education-indonesia-progress-more-wor k-be-done.