- Home

- Capabilities

- ACTIO Hub

- About Us

- Connect with Us

- AP Library

by Setyawati Fitrianggraeni, Tiyana Sigi Pertiwi, Alicia Daphne Anugerah, Orima Melati Davey, Christou Imanuel*

It has become increasingly apparent that Indonesia is eager to advance its position within the global market of ship recycling industry. At the start of 2025, the Ministry of Transportation’s Directorate of Vessels and Maritime Affairs conveyed the importance of the fact that the Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound of Recycling of Ships 2009 (“HKC”) will soon enter into force on 26 June 2025.[1] The Head of Directorate expressed that one of the primary motivation behind Indonesia’s attention to the HKC is to ensure their global compliance to ensure human safety, protection of marine of environment, and waste management due to ship recycling activities covered by this Convention.[2]

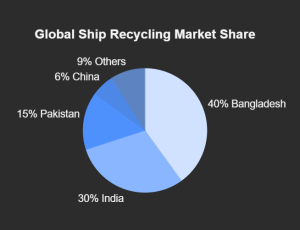

Figure 1: OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers. Ship Recycling: An Overview. April 2019 No. 68. As of 2017, the major 4 countries accounting for around 91% of global demolition volumes is shared by Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, and China.

In essence, the responsibility for ensuring compliance with international coventions lie on the contracting states, i.e., the relevant national authorities in each flag state flown by the vessels.[3] Since Indonesia is not yet a party to the convention, for national shipping companies, charterers and shipowners, the entry into force of the HKC may seemingly be irrelevant for vessels sailing under the Indonesian flag. However, port states are also entitled to control foreign ships visiting their ports to ensure that any deficiencies found are rectified before they are allowed to sail. In this regard, the Operational Director of BKI[4], warns that non-compliance to the ship recycling standards set by the HKC may lead to detention of non-complying Indonesian vessels berthing at ports in countries already complying with the safety and environmental standards set by the Convention[5].

Further, although Indonesia has yet to officially ratify the HKC, as a matter of fact, vessels of 500GT and over are required to comply with the safety standards of HKC by the Regulation of Ministry of Transportation No. PM 24 Year 2022.

It is imperative to be understood that the aim of the HKC cannot be reached solely by state compliance only, and that it also has implications to be observed by all stakeholders in the shipping and ship recycling industries. Thus in order to ensure a robust coherency and in preparation for when the HKC comes into effect, the stakeholders in Indonesia should have sufficient understanding of the core provisions of the HKC along with its implications. This would serve to better enhance the competitiveness of Indonesia’s ship recycling industry in the international market[6], compared to other current global major players in the ship recycling industry already in compliance with the standards set in the HKC at the time of its entry into force in June 2025.

On a national level, having all stakeholders comply with the provisions of the HKC would hopefully ensure Indonesia’s position to stay within the Tokyo MoU’s annual white list[7], as an indicator of the high safety and security aspects observed by the shipping industry in Indonesia. According to the Directorate General of Maritime Transport, white-listed flag states by the Tokyo MoU would have stronger diplomatic position when negotiating relevant international maritime regulations in the global stage.

Prior to the HKC, the international ship recycling industry is regulated by the Basel Convention.[8] Specifically, the Basel Convention’s relevance is since the act of shipbreaking or dismantling of a vessel at the end of its life cycle often results in harmful materials, which is considered as hazardous waste under the convention. However, the focus of Basel Convention is primarily to regulate the transboundary movement of hazardous waste.[9]

Under the Basel Convention, control of such transboundary movement of hazardous waste due to ship recycling is through the consent for shipment between the authorities of the exporting country with the authorities of the importing country, and with the involvement of the authorities of any transit State, thereby preventing illegal exports of the same to countries which are unable to properly dispose said hazardous waste under adequate safety and environmental standards.[10] In order to strengthen protection to developing countries, the parties to the Basel Convention adopted the Basel Ban Amendment, prohibiting the export of hazardous waste from OECD countries to a non-OECD country. Hence issue arises when the shipbreaking facility in question is located in a non-OECD contracting state.

Ship recycling is defined by the HKC as :[11]

“the activity of complete or partial dismantling of a ship at a Ship Recycling Facility in order to recover components and materials for reprocessing and re-use, whilst taking care of hazardous and other materials, and includes associated operations such as storage and treatment of components and materials on site, but not their further processing or disposal in separate facilities.”

Based on the above, the regulations set by the HKC aims to cover every aspect of the life of the ship (from “cradle to grave”) which was not fully facilitated by the Basel Convention. To put it briefly, ship recycling entails the act of dismantling or breaking of a vessel at the end of its life, and such process should be ensured to be conducted in an environmentally sound manner.

In terms of environmental and occupational health regulations, the HKC also goes beyond covering the standards previously set by the Basel Convention. Pursuant to the considerations of the HKC, the main objective of the Convention is to “effectively address, in a legally-binding instrument, the environmental, occupational health and safety risks related to ship recycling, taking into account the particular characteristics of maritime transport and the need to secure the smooth withdrawal of ships that have reached the end of their operating lives.”[12]

Another difficulty with regard to the regulation of ship recycling under the Basel Convention alone is the determination of when a ship intended to be dismantled is considered to be a waste which falls under the Basel Convention. Under the HKC, the notification requirements on the intent and reporting process for ship recycling is further regulated as follows[13]:

The core aim of the HKC can be further observed in the following key provisions:

a. Inventory of Hazardous Materials

Once the HKC comes into force, a vessel that flies the flag of the contracting states of the Convention, will be mandated to maintain and carry an Inventory of Hazardous Materials (“IHM”) on board, which is a list identifying the approximate quantity and location of hazardous materials onboard, will be required for all ships over 500GT.[14] IHM consists of 3 (three) parts (Part I – hazardous materials contained in the ship’s structure and equipment; Part II – operationally-generated waste; Part III – stores), wherein parts II and III should be prepared prior to recycling. This implies that during the entire lifespan of the vessel (during the operation of the vessel and during the recycling process), there is an obligation to ensure that the vessel is free from any hazardous materials specified in Appendix I of the HKC.

b. Ship Recycling Facilities

Not only the ship owner, the HKC also targeted the ship recycling industry. Under the Regulation 9 of the Convention, a ship recycling facility must develop a Ship Recycling Facility Plan.[15] The Ship Recycling Facility Plan must include information concerning the establishment, maintenance, and monitoring of Safe-for-entry and Safe-for-hot work conditions, including on the type and amount of materials including those identified in the IHM will be managed.[16] Furthermore, ships shall only be recycled at ship recycling facilities authorized by the competent authority. Governments of each the contracting states will be required to ensure that recycling facilities under their jurisdiction comply with the HKC.

c. Prevention of Adverse Effects to Human Health and the Environment

The Hong Kong Convention aims to ensure the safety and well-being of workers in ship recycling facilities. Ship dismantling is recognised as a high-risk occupation due to the potential exposure to hazardous atmospheres and unsafe working environments. This concern is reflected in the Hong Kong Convention’s requirement for ship recycling facilities to include the prevention of adverse effects on human health and the environment in the ship recycling plan.[17]

d. Surveys and Certifications

The process of design, construction, survey, certification, operation and recycling of ships shall be conducted in accordance with the provisions of the HKC. IHM will need to be developed and maintained during the entire life of the vessel until prior to recycling. Ships will be required to have an initial survey to verify the IHM, renewal surveys during the life of the ship, and a final survey prior to recycling. HKC provides that an International Ready for Recycling Certificate shall be issued after successful completion of the final survey. International Certificate on IHM shall not exceed 5 years while an International Ready for Recycling Certificate shall not exceed 3 months. [18]

Although Indonesia has ratified the Basel Convention through Presidential Decree No. 61 Year 1993, Indonesia has yet to ratify the HKC. Even so, some of the objectives and key provisions of the Convention is already present in the current national legal instruments governing ship recycling activities in Indonesia, such as follows:

a. Law Number 17/2008 as amended by Law Number 66/2024 (New Shipping Law 66/2024)

Law Number 17/2008 of Shipping as amended by Law Number 66/2024 is a milestone for shipping regulation for Indonesia, as it is the first shipping law which mandates the protection of marine environment. One of the key areas within the scope of marine environment protection involves ship recycling, which must be conducted using an environmentally sustainable approach.[19] Ship recycling that is not carried out in accordance with an environmentally sound approach is subject to criminal sanctions, including a maximum imprisonment of two years and a fine of up to Rp300,000,000.00 (three hundred million rupiah).[20]

b. Regulation of Ministry of Transportation No. PM 24 Year 2022 on Prevention of Maritime Environmental Pollution

This Ministry Regulation represents the spirit of HKC. Although Indonesia has not yet ratified this Convention, this regulation integrates the ship recycling standards as outlined in the HKC. In particular, Art. 51(1) explicitly stipulates that Indonesian flag state vessels with a gross tonnage (GT) of 500 or more sailing in all seas are required to comply to the provisions of the HKC.[21] As for Indonesian flag state vessels of 100GT or more sailing in the Indonesian waters, PM 24/2022 also further regulates ship recycling to be complied for the same. Several key instruments from the HKC which are also introduced in the PM 24/2022 with regard to the ship recycling procedures includes obligation to have IHM, reporting and certifications, and Ship Recycling Facility Plan for ship recycling facilities.

In essence, to ensure that the recycle of ships will be conducted in a safe and environmentally sound manner under the HKC, compliance during the entire lifespan of the vessel (from the design, construction, survey, certification, operation and recycle process) must be carried out by all stakeholders in Indonesia (e.g., shipowners, shipping companies, charterers, survey and certification agency, maritime authorities, ship building and ship recycling industries).

However, there are still other challenges to be faced by Indonesia, should they wish to further advance their ship recycling industry in order to compete with the global market, alongside other countries already party to the Convention. This includes managing the cost of compliance with the Convention, since the cost of technology to conduct environmentally sound ship recycling is higher. Indonesia also needs to commit to generally increase their ship recycling capacity if the Government’s vision is to materialize.

Setyawati Fitrianggraeni serves as Managing Partner at Anggraeni and Partners in Indonesia and Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Law, University of Indonesia, while pursuing her PhD at the World Maritime University in Malmö, Sweden, where she leads a legal research team focused on Ocean Maritime Climate. The team includes researchers Orima Melati Davey, Christou Imanuel Siregar and Alicia Daphne Anugerah, alongside Knowledge Lawyer Tiyana Sigi Pertiwi.

P: 6221. 7278 7678, 72795001

H: +62 811 8800 427

Anggraeni and Partners, an Indonesian law practice with a worldwide vision, provides comprehensive legal solutions using forward-thinking strategies. We help clients manage legal risk and resolve disputes on admiralty and maritime law, complicated energy and commercial issues, arbitration and litigation, tortious claims handling, and cyber tech law.

S.F. Anggraeni

Managing Partner

Tiyana Sigi Pertiwi

Knowledge Lawyer

tiyana.si@ap-lawsolution.net

Orima Melati Davey

Legal Researcher

Ocean-Maritime-Climate Research Group

orima.md@ap-lawsolution.net

Christou Imanuel Siregar

Legal Researcher

Ocean-Maritime-Climate Research Group

christou.is@ap-lawsolution.net

Alicia Daphne Anugerah

Legal Researcher

alicia.da@ap-lawsolution.net